Últimas notícias

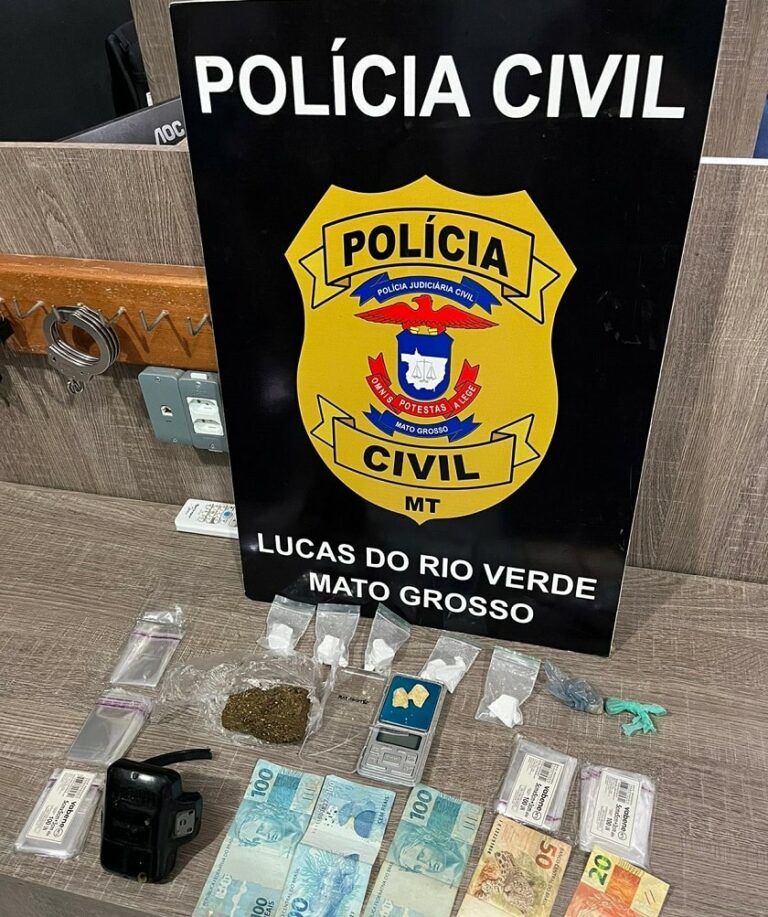

Dois foragidos da Justiça são presos pela Polícia Civil em Lucas do Rio Verde

Na quarta-feira (10/04), a Polícia Civil prendeu dois foragidos da Justiça, um deles em…

Destaques

Wellington vê como algo natural a união entre o PL e o MDB

O senador Wellington Fagundes, figura proeminente do PL e membro de longa data do partido,…

Ciência e Saúde

EFICIÊNCIA NA SAÚDE | Ala pediátrica do Hospital Regional de Sinop atendeu 764 pacientes em menos de seis meses

A ala pediátrica do Hospital Regional de Sinop prestou atendimento a 764 pacientes durante o…

Esportes

JOGO DE IDA- Cuiabá vence o União, por 1 a 0, e tem vantagem para o jogo de volta

Na primeira partida da final do Campeonato Mato-Grossense de 2024, o Cuiabá Esporte Clube…

Cidades

Tesouro | Aniversário de 70 anos será marcado pelo acender das luzes de Natal e chegada do Papai Noel

No próximo domingo, 10 de dezembro, Tesouro celebra seu 70º aniversário de emancipação. Para…

Cidadania e Cultura

Reabertura do Espaço de Identificação Infantil na Próxima Semana Após Reforma

Está previsto que, a partir do próximo dia 22, os serviços no Espaço de Identificação…

Todas as notícias

Brasil condena qualquer ato de violência, diz chanceler sobre Irã

O ministro das Relações Exteriores do Brasil, Mauro Vieira, expressou a condenação do…

União contrata atacante e busca reforços para disputa da Série D

O União está empenhado em fortalecer seu elenco para encarar a Série D do Campeonato…

Dois foragidos da Justiça são presos pela Polícia Civil em Lucas do Rio Verde

Na quarta-feira (10/04), a Polícia Civil prendeu dois foragidos da Justiça, um deles em…

Após cobrança em reunião ministerial, Lula faz afago em ministra da Saúde

Após emocionar a ministra da Saúde durante uma reunião ministerial, o presidente Luiz Inácio…

Botelho e lojistas debatem ações de combate aos furtos de fios de cobre e violência no centro de Cuiabá

Atualmente, a segurança no Centro Histórico é uma questão preocupante que afeta diretamente…

Detran instala 106 painéis solares na sede em Cuiabá para reduzir gastos com energia elétrica

O Departamento Estadual de Trânsito de Mato Grosso (Detran-MT) está avançando na adoção de…

JOGO DE IDA- Cuiabá vence o União, por 1 a 0, e tem vantagem para o jogo de volta

Na primeira partida da final do Campeonato Mato-Grossense de 2024, o Cuiabá Esporte Clube…

Anvisa autoriza registro de vacina que previne bronquiolite em bebês

A Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (Anvisa) deu sinal verde para o registro da…

IPTU 2024 pode ser pago até o dia 10 de abril com 20% de desconto ou parcelado em Rondonópolis

Os moradores de Rondonópolis têm até o dia 10 de abril para quitar o IPTU 2024. Pagamentos…

Primeira-dama de MT participa da adesão de Barra do Garças ao SER Família Criança que levará nome de sua mãe

Durante a visita da primeira-dama do Estado, Virginia Mendes, à cidade de Barra do Garças,…

Primeira-dama de Cuiabá acredita no Qualifica 300 para retomada da economia e empregos

A esposa do prefeito, Márcia Pinheiro, está otimista quanto ao impacto do programa Qualifica…

Cientistas chineses criam mutação do coronavírus que é 100% letal

Testes conduzidos com uma variante mutante do coronavírus (SARS-CoV-2) revelaram uma taxa de…